I want to thank Captain Bowen’s great-great-granddaughter, Mary Robinson for helping me share her ancestor’s story, presented here in several parts, of which this is the first.

The 28th New York Volunteers lost heavily at the Battle of Cedar Mountain.#1 It was the defining episode of the regiment’s two year history, and they memorialized it in writings, battlefield monuments and veteran re-unions. The story of Captain Erwin A. Bowen figures prominently amidst these engaging human interest stories.

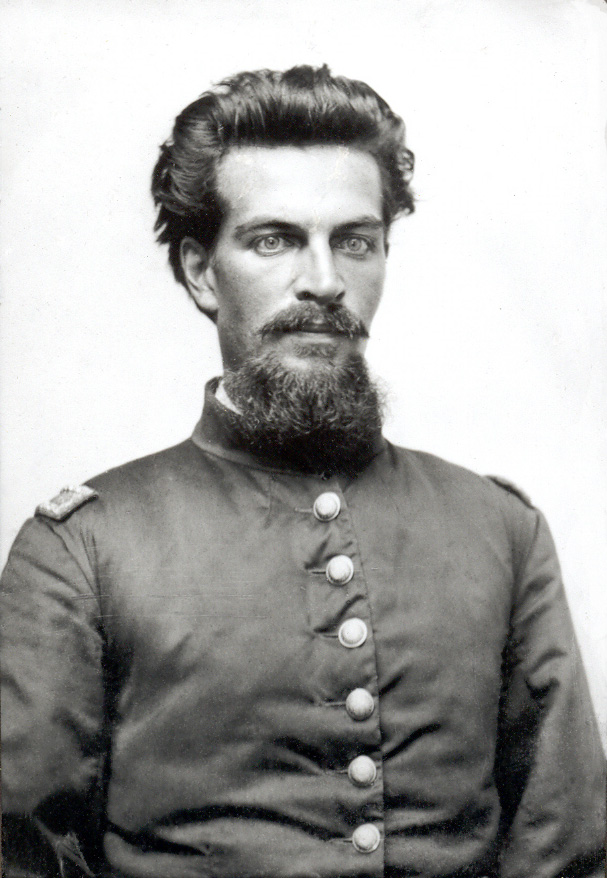

Erwin A. Bowen was born to farmer parents near Medina, New York in 1835. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted, May 22nd 1861 as Captain, of Company D, 28th New York Volunteer Infantry. He was 26 years old. Experience as a lieutenant in the New York State Militia gave credibility to his military qualifications. Charles W. Boyce, regimental historian of the 28th, described Bowen as a “man of fine physique, tall and erect, with black hair, quick flashing eyes and a commanding voice.” He was a strict disciplinarian, but off duty “no one could be kinder or more approachable.”#2

A chance appointment as Provost Marshal in the Virginia city of Harrisonburg would yield unforeseen benefits for Captain Bowen at a time when they were most appreciated.

In the Spring of 1862, the 28th New York Volunteers advanced into the Shenandoah Valley as part of Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks command. They occupied Martinsburg on March 2nd. Banks’ slowly continued up the valley 12 miles to Bunker Hill, March 5th; then another 12 miles to Winchester, March 12th.

Charles Boyce wrote, “This beautiful valley never appeared so charming again during the War, as on this first entry of the army in the spring of 1862. …The citizens of Winchester were very pronounced in their Southern feelings. They exhibited their hatred to the Union soldiers on all occasions.”#3

The regiment stayed two weeks here then tromped eastward through Berryville to the Shenandoah River, on March 22nd. Their division commanded by General Alpheus S. Williams was ordered across the Bull Run Mountains to join the rest of the army at Centreville. On the way they learned the bridge over the river just outside Berryville was out, which delayed further progress. But while waiting for repairs, they were ordered to return to Winchester the next day.

General Stonewall Jackson, seeing a chance, attacked Winchester on March 23rd after William’s division had marched away. Stonewall’s attack was repulsed and he slowly retreated southward. William’s Division returned to Winchester and began an even slower pursuit of Jackson.

Taking their time, with stops and starts the division arrived at Harrisonburg on April 25th. Colonel Turner Ashby’s Rebel Cavalry repeatedly harassed them during the advance up the Valley. At Harrisonburg, General Williams set up his headquarters in the posh Bank of Rockingham building. Captain Bowen was appointed Provost Marshal of the city, and his Company D, was appointed Provost Guard. Captain Bowen set up his headquarters at the Court-House. The rest of the division marched south another 5 miles.

At Harrisonburg Captain Bowen forever sealed his reputation as an honorable man, with the local people.

“At first the citizens were very much alarmed, …they had little respect for our army, which had come into their midst declaring martial law and taking official possession of their town.” They had every reason to fear that “our visit would be one of pillage.” #4 But the Captain soon changed their minds.

Under Captain Bowen’s able management, “the streets were cleaned, the post-office was opened, the printing press was started, saloons were closed, and the best of order was preserved. The citizens all acknowledged that the good order was fully equal to that maintained in times of peace.”

“… By many acts of kindness the people were shown that their rights as citizens would be protected, and that the army was not one of invasion for plunder and murder.”#5

When a Confederate officer was killed in nearby fighting, his widow requested to have the body of her husband brought home to the city for proper burial in the village cemetery. “This, in the exciting times of war, was an unusual request,” Boyce said. When Bowen sought permission from the Union general commanding the area the general incredulously wrote back “why –– –––– do you ask for such an order!” Whereupon Bowen filed the request again with the following endorsement: “I did not enter the service to fight dead men, women, or children.”

The order was issued. Bowen even provided the woman with an escort and an ambulance to bring her husband’s body home. #6

A proper burial was of extreme importance, culturally, and this action would have been significant. Here is a brief commentary from a more scholarly source, author Drew Gilpin Faust’s work, “This Republic of Suffering”:

Addressing the importance of burial, Henry Raymond, founder of the New York Times, wrote an essay on the subject published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 1854. “There has ever been, in all places, in all ages, among all classes and conditions of making, a deep-feeling in respect to the remains of our earthly mortality.” In the body, remains “something of the former self-hood.”

“And in the terms of prevailing Protestant doctrine, something of the future and immortal selfhood as well.” “Such understandings of the body …mandated attention even when life had fled; it required what always seemed to be called “decent” burial…”#7 [End Quote.]

So many soldiers on both sides died nameless in unmarked graves. This gesture, and others, by Captain Bowen must have made a lasting impression.

Boyce wrote, “When the command moved from Harrisonburg, soon afterwards, Captain Bowen left there many true friends.”

General William’s division remained near Harrisonburg until May 5th, when due to insufficient numbers they were recalled to New Market, 19 miles north. Boyce wrote, “The men were very sorry to leave that beautiful city…”#8

Captain Bowen’s term as Provost Marshal had lasted just ten days. But those 10 days forged a life-time of friendships, the results of which would play out in an interesting turn of events four months later when Captain Bowen found himself a prisoner of war.

GENERAL POPE’S CONTROVERSIAL ORDERS

In the late Spring of 1862, frustrated with General McClellan’s philosophy and performance, which could be described as, to gently coerce wayward Southerners back into the Union with a show of overwhelming military force, President Lincoln and Congress decided upon a harder war policy. The new policy was announced in part, through a series of General Orders issued by newly appointed Major-General John Pope, commander of the Army of Virginia, organized June 26.

General Order No. 5, issued July 5th directed the Army of Virginia to “subsist off the land.” “Vouchers will be given to the owners, stating …that they will be payable at the conclusion of the war, upon sufficient testimony being furnished that such owners had been loyal citizens of the United States since the date of the vouchers.” (Good luck with that.)

General Order No. 7, issued July 19th dealt with the growing and persistent problem of guerrillas operating along the fringe and rear of the Federal armies. Residents living “along the lines of railroad and telegraph and along the routes of travel in rear of the United States forces are notified that they will be held responsible for any injury done to the track, line or road, or for any attacks upon trains or straggling soldiers by bands of guerrillas in their neighborhood…Evil-disposed persons in rear of our armies who do not themselves engage directly in these lawless acts encourage them by refusing to interfere or to give any information by which such acts can be prevented or the perpetrators punished.”

“…It is therefore ordered that wherever a railroad, wagon road, or telegraph is injured by parties of guerrillas the citizens living within 5 miles of the spot shall be turned out in mass to repair the damage, and shall, beside, pay to the United States in money or in property, to be levied by military force, the full amount of the pay and subsistence of the whole force necessary to coerce the performance of the work during the time occupied in completing it.

“If a soldier or legitimate follower of the army be fired upon from any house, the house shall be razed to the ground, and the inhabitants sent prisoners to the headquarters of this army. If such an outrage occur at any place distant from settlements, the people within 5 miles around shall be held accountable and made to pay an indemnity sufficient for the case.

“Any persons detected in such outrages, either during the act or at any time afterward, shall be shot, without awaiting civil process.”

Finally, General Order No. 11, dated July 23rd directed officers in the Army of Virginia to “arrest all disloyal male citizens within their lines within their reach.

“Such as are willing to take the oath of allegiance to the United States and will furnish sufficient security for its observance shall be permitted to remain at their homes and pursue in good faith their accustomed avocations. Those who refuse shall be conducted South beyond the extreme pickets of this army, and be notified that if found again anywhere within our lines or at any point in rear they will be considered spies, and subjected to the extreme rigor of military law.

If any person, having taken the oath of allegiance as above specified, be found to have violated it, he shall be shot, and his property seized and applied to the public use.”#9

The orders were controversial among many in the North, but needless to say, these orders did not resonate well with the Confederate authorities.

They declared any captured officers of General Pope’s army, would be treated as common criminals rather than prisoners of war. And, they kept their promise.

The Richmond Inquirer, August 12, 1862 reported:

NOT PRISONERS OF WAR. — The officers who arrived on yesterday, from Gordonsville, twenty-eight in number, and who were captured by Gen. Jackson on Saturday, will not be considered prisoners of war, so long as the recent and uncivilized orders of Gen. Pope remain unrepealed. They have all, Gen. Prince included, been placed in the Libby prison, and will in a few days be separately confined, to be treated, and finally punished as felons, should the brute Government of the North persist in claiming the right to murder and pillage.#10

Against this backdrop is Captain Bowen’s story.

The same day the above article appeared in the Richmond Inquirer, August 12, 1862, the Richmond Dispatch reported the arrival of captured prisoners from the recent Battle of Cedar Mountain. Included on the list of names is Captain Erwin A. Bowen.

RICHMOND DISPATCH, August 12, 1862.

Arrival of Prisoners from Pope’s Army. — The Central train that arrived at 4 o’clock yesterday morning brought to this city three hundred and three of Pope’s Hessians, captured on Saturday, near Southwest Mountain, by the advance forces of Gen. Jackson’s army. Accompanying the above were Brig.-Gen. H. Prince, a Yankee General, and twenty seven commissioned officers, who, together with the men, were lodged in the Libby Prison. Prince, for a few hours, was lodged at the Exchange Hotel. The President’s recent proclamation declared Pope and his commissioned satellites to be without the usages of warfare, and not entitled to the privileges of ordinary prisoners of war. Orders were issued to place all of the captured officers in close confinement. At the Libby Prison they were put with the deserters and other persons to whom infamy attaches. An examination was made into the condition of the county jail, with a view to their incarceration there; but the structure was deemed unsafe. They have not been permitted to associate with the Federal officers, and appear very downcast at the prospect before them. — We append a list of the officers captured at Southwest Mountain, as follows:

Capt G B Halstead, Adj’t General Augur’s division

2d Lieut Vealor Moses, 109th Penn.

Col Geo D Chapman, 5th Conn.

1st Lieut S J Widvey, 3d Wisconsin.

Capt W D Watkins, Ass’t Adj’t Gen’l, Williams’s division.

Capt H S Russell, co H, 2d Mass.

Capt J H Vanderman, co K, 66th Ohio.

2d Lieut Wm Alister, co H, 28th N. Y.

2d Lieut J Long, co H, 28th N. Y.

1st Lieut J D Belloiexley, co D, 10th Me.

1st Lieut H N Greatrake, co B, 46th Penn.

1st Lieut M P Whitney, co B, 5th Conn.

Capt P Griffith, co A, 46th Penn.

2d Lieut Chas Sydnor, co D, 8th U. S. Infantry.

1st Lieut H C Egbert, co G, 12th U. S. Infantry.

2d Lieut J D Woods, co B, 28th N. Y.

1st Lieut A A Chinery, co E, 5th Conn.

1st Lieut T B Gorman, co H, 46th Penn.

2d Lieut A W Selfridge, co H, 46th Penn.

2d Lieut Otis Fisher, co B, 8th U. S. Infantry.

2d Lieut Wm N Green, co A, 102d N. Y.

2d Lieut H Walker, co I, 3d Md.

Capt E A Bowen, co D, 28th N. Y.

Maj E W Clarke, 28th N. Y.

1st Lieut Wm M Kenyon, co G, 28th N. Y.

2d Lieut J D Ames, co K, 28th N. Y.

2d Lieut Chas Doyle, co D, 5th Conn.

The next part of this story will be given in Captain Bowen’s own words.

To be continued…

FOOTNOTES

1. 28th NY 59% casualties

Present in Engagement: 18 Officers & 339 Enlisted men. [357 total]

1 officer, 20 enlisted men killed, 6 officers, 73 enlisted men wounded; 10 officers, 103 enlisted men taken prisoner, [213 total, K, W, Captured.] From, “A Brief History of the Twenty-eighth New York State Volunteers,” Charles William Boyce, Buffalo, N.Y., 1896.

2. Article by Bob Marcotte, in the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, Sunday, March 25, 2012. The author may have had a source I don’t have titled, “A story of the Shenandoah valley in 1862. The first Provost-Marshal [Erwin A, Bowen] of Harrisonburg, Va.” BandG III (1894) 243-8, by Charles William Boyce.

3. Boyce, p. 24-25.

4. Marcotte article.

5. Boyce, p. 27

6. Marcotte article.

7. Drew Gilpin Faust, “This Republic of Suffering,” p. 62. Vintage Civil War Library Edition, (Random House) 2009. Faust cites Henry Raymond, “Editor’s Table,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 8 (April 1854): 690 – 693. And, On body and death, Caroline Bynum, The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), and Bynum, Fragmentation and Redemption: Essays on Gender and the Human Body in Medieval Religion (New York: Zone Books, 1991).

8. Boyce, p. 27.

9. General Orders cited from “The Rebellion Record,” Vol. 12, p. 362-362.

10. Richmond Newspaper articles accessed at civilwarrichmond.com