Introduction

General N.P. Banks initiated the fight at Cedar Mountain, against Stonewall Jackson, and though his troops fought with incredible courage and achieved at first, remarkable success, the end result was devastating. His corps was essentially out of service for the next 3 weeks of the war until they were heavily re-enforced with new regiments. General Banks never wrote an official report on the battle he instigated. Banks was primarily a politician, and most concerned with his public reputation, which suffered after the battle. In December of 1864, while giving testimony in Washington, D.C. to the Committee on the Conduct of the War, regarding the Red River Expedition, he brought up of his own volition, the subject of his marching orders from General Pope, on the morning of August 9, 1862, the day of the battle of Cedar Mountain. His statement meant to justify his decision to attack Jackson. When General John Pope, who was serving in the West, accidentally learned of this testimony, he replied to the committee in the form of a long letter.

This post presents the testimony published in the following volume: “Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War: at the second session Thirty-eighth Congress;” by, United States Congress, Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War; Wade, B. F. (Benjamin Franklin), 1800-1878; Gooch, Daniel Wheelwright, 1820-1891; United States, Congress (38th, 2nd session: 1864-1865). Publication date 1865.

That said, these reports are difficult to locate. They are in the Miscellaneous Section (p. 44-54) at the end of the volume that contains the following reports: Sherman-Johnston. Light-Draught Monitors. Massacre of Cheyenne Indians. Ice Contracts. Miscellaneous.

BATTLE OF CEDAR MOUNTAIN

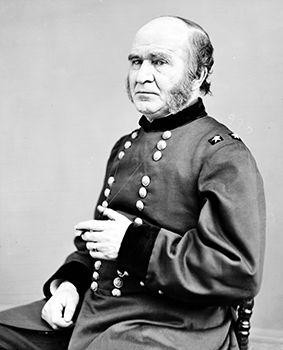

Testimony of Major General N. P. Banks.

WASHINGTON, D. C., December 14, 1864.

Major General N. P. BANKS sworn and examined.

Having testified in relation to the Red River expedition the witness said: There is another subject upon which I wish to make a statement. I am sorry to say that I have made very few reports; and, as so many people report things that do not happen, it is perhaps excusable if there is one man who does not report things that do happen. I had an engagement at Cedar mountain on the 9th of August, 1862, which was a part of General Pope’s campaign. I desire to call the attention of the committee to that for a moment, for this single reason, it has never been explained, and I have never had a chance to put it on record before, except in a report to the War Department, from whence no information comes to the public at all; and it leaves me under a wrong impression in the public mind, as you will see when I have made my statement. I was in command of a corps in August, 1862, in the Shenandoah valley. I was ordered to General John Pope’s command, in the Rappahannock valley. Under his orders I moved to Culpeper on the 9th day of August, arriving there about seven o’clock in the morning. His headquarters were in the town, and my command was in the outskirts of the town. Immediately on my arrival at Culpeper, I received orders from General Pope to move to the front, which was six miles in advance of Culpeper, where a brigade of my command had been stationed for a week, occupying the outposts under General Crawford. That order was received at eight o’clock, and in thirty minutes was countermanded. At 9.45 on the same day I received another order from General Pope to move immediately to the front. The order was in these words—I will read from the original paper, in the handwriting of my adjutant general Colonel Pelouze:

“CULPEPER, 9.45 a.m., August 9, 1862.

“From Colonel Lewis Marshall: General Banks will move to the front immediately, assume command of all the forces in the front, deploy his skirmishers if the enemy approaches, and attack him immediately as soon as he approaches, and be re-enforced from here.”

This order was given to me verbally by the officer who brought it. He delivered it in the presence of five of my staff officers. I immediately said to him, “You will please give this order to my adjutant general, that he may reduce it to writing.” Colonel Pelouze was sitting at a table at the moment, and the officer who bore the order stepped up and repeated it to him, and it was written from his lips as he pronounced it. Colonel Pelouze then read the order to him in order to see if it was correct, and he approved it. This took place in the presence of five of my staff officers and some other officers who did not belong to my command. Within an hour from 9.45 my troops were on the march. We reached the point indicated, five miles to the front, between one and two o’clock. On their way out I left the head of my column and went to General Pope’s headquarters, he occupying then a house belonging to Mr. Wallach, the editor of the “Evening Star” in this city. I told General Pope that my troops were on their way, and asked him if he had any other orders. He said, “I have sent an officer acquainted with the country who will designate the ground you are to hold, and will give you any instructions he may deem necessary.” I continued my march, and reached the ground occupied by General Crawford, who occupied a line in front of the enemy. On my arrival there I met Brigadier General Roberts, chief of staff to General Pope. I said to him that General Pope had told me that he would indicate the line I was to occupy. Said he, “I have been over this ground thoroughly, and I believe this line”—meaning the one which General Crawford’s brigade then held—”is the best that can be taken.” I concurred with him in that opinion, and placed my command there. I had six thousand men.

The enemy had all the morning been moving his forces, with a view to action, as I learned from General Crawford. Slaughter’s mountain, or, as we call it, Cedar mountain, was in the vicinity of our position. There were dense woods in front, occupied by the enemy. General Crawford occupied a line a little to the rear and centre of an open plain between us and the enemy. My force took up the position which was indicated by General Roberts, who had looked over the ground. It was the best position for attack, which was the object indicated by my orders. If I had been instructed simply to act upon the defensive we should have taken a line in the woods behind Cedar creek, because it have concealed our forces and given us the benefit of the creek—where, by the way, when we retired at nightfall, we lost one piece of artillery—but our object being different, I was instructed to take this line. The enemy had been moving troops down to the rear of the mountain during the day. It was supposed that they would occupy a hill, and move upon us from the left. We made a reconnoissance from the front. I went down to the front with some officers, and we were impressed with the idea that, while they were openly moving on the other side, they were coming down upon the right; and if they got possession of those woods and attacked us, we would be obliged to fall back. Being impressed with the feeling that they were coming down on our right, I directed Brigadier General Crawford to send one regiment to feel them. They in the mean time had sent a line of skirmishers from the woods out to the front, and were gradually creeping up. General Crawford went up with a regiment to the right, and said, “The enemy begins to appear here; I must have more force.” I sent him a brigade. The enemy by that time had massed his forces on our right—his left—and was moving forward, and began an attack upon us, when my force encountered him. The battle had been going on with artillery from two until four o’clock. About five o’clock, which is the usual time for them to make an attack, they made a desperate attack upon our right. Of course, we had to strengthen that with all our force. It is certain that General Jackson was there with twenty-three thousand men, for he was in that neighborhood. Our troops never fought better in the world than there. They had been retreating up to that time, and panted for a fight. The battle raged for two hours, and until the combatants were separated by the darkness, with as much stubbornness as ever men fought in the world. Alexander’s troops never fought better. They held their position until dark; but the enemy was so much stronger that it was impossible for us to advance. In the evening, after dark, they fell back to the line they had occupied in the day-time, General Pope coming up after dark with his command. I say it was after dark, because, after my troops were in line, understanding General Pope was coming up, I rode to the rear to meet him, and passed him, because it was so dark that I could not distinguish him. I sent to General Pope every hour, from one or two o’clock, information of what was transpiring. I did not say the enemy was in force because I did not know it; and I was a little desperate, because we supposed that General Pope thought we did not want to fight. General Roberts, when he indicated the position, said to me, in a tone which it was hardly proper for one officer to use to another, “There must be no backing out this day.” He said this to me from six to twelve times. I made no reply to him at all, but I felt it keenly, because I knew that my command did not want to back out; we had backed out enough. He repeated this declaration a great many times, “There must be no backing out this day.” At the crisis of the battle he left. It was really and honestly a drawn battle. We held our line, but we had suffered very severely. The enemy was stronger than we were, and we knew that we could not overcome him. Late at night General Pope came up with his forces. In the morning the enemy retreated, recrossed the Rappahnnock, and did not advance again for ten days after the battle at Cedar mountain, when the same troops came forward on the other side of the river and made a detour up towards Washington, with the whole of that army. By that time General McClellan had been able to get his forces in the neighborhood of Washington, and we were enabled to meet them after a fashion. I regard that that battle prevented the advance of the enemy’s forces for some days.

What I want to say is that this battle was fought under positive orders in the presence of the chief of staff or General Pope; but I am sorry to hear that he represents in his report that it was a battle fought honestly by me, but against orders and without being expected by him. Here is the original order, which I will read again:

“From Colonel Lewis Marshall: General Banks will move to the front immediately, assume command of all the forces in the front, deploying his skirmishers if the enemy approaches, and attack him immediately as soon as he approaches.”

We were obliged to fight or retreat, and no battle has ever been fought in better faith or in a better manner. We were five thousand men against twenty-five thousand in those woods and on that hill. It was a well-fought battle.

Letter of Major General Pope to Hon. B. F. Wade, chairman of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, with accompanying papers and testimony concerning the battle of Cedar mountain, August 9, 1862.

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE NORTHWEST,

Milwaukie, Wisconsin, January 12, 1865.

SIR: It has come to my knowledge that Major General Banks, while in Washington city recently on leave of absence with one or two of his staff officers, gave some testimony before your honorable committee concerning a portion of the battle of Cedar mountain.

Of course your honorable committee would not permit an ex parte statement on so important a subject to be recorded in their proceedings without notifying and examining other officers concerned, and without giving the whole subject that careful and full investigation which justice and fair dealing demand, and which has characterized the proceedings of your committee hitherto.

In this view, and upon one point concerning which General Banks has given some testimony, I desire to invite your attention to the following facts, which I submit as my own testimony on the subject. Whilst it would not be consistent, probably, with the interests of the public service that I should, for the present, be called away from my official duties in this department, I would respectfully request that the officers herinafter mentioned be summoned to give their testimony in the case.

I understand that General Banks, seeks, by his testimony and that of one or two of his staff, to rid himself of the responsibility of the battle of Cedar mountain by attempting to show that he acted under my orders in making the attack.

The facts herein stated, and which the testimony of the officers herinafter mentioned will fully establish, will plainly exhibit to your committee the value of General Banks’s plea, and of the testimony he brings forward to justify it.

General Banks alleges that he received a verbal message from me from the lips of Colonel L. H. Marshall, an officer on my staff, in the following words, viz: “General Pope directs that you move to the front with your corps, and take up a strong position at or near the point occupied by Crawford’s brigade of your corps. If the enemy advances against you, you will push your skirmishers well out and attack. Re-enforcements will be sent forward from Culpeper.”

Upon this order, which I never gave, but which General Banks says he received, he bases his justification in leaving the strong position he was ordered to take up, and in advancing two miles (nearly) to attack an enemy well posted and in superior force.

What possible object could there be in ordering General Banks to take up a strong position against the advancing enemy, when the moment that enemy advanced he was to leave it and march forward to attack? In this case, too, it was not the enemy that advanced against Banks’s strong position, but Banks who advanced against the enemy’s chosen position.

The movements of the army for concentration to fight Jackson were perfectly well known to everybody in the army, and of necessity to General banks. His corps was pushed forward to occupy and hold a strong position, behind which the concentration of McDowell and Sigel was to be made.

I venture to point out the absurdity of General Bank’s interpretation of the verbal order which he says he received, but which in no manner authorizes his forward movement against Jackson, because it is manifest that much dependence is placed upon the superficial reading often given to such papers. I submit also an official letter from Colonel Marshall on the subject, from which it is manifest that I neither gave any order through hm which authorized General Banks to leave his strong position and attack the enemy, nor did Colonel Marshall intend to convey any such idea to General Banks.

Whatever, however, may have been the facts in reference to Colonel Marshall’s delivery of the verbal order referred to, and whatever that order may have been as delivered, I do not perceive that it has the slightest bearing upon the question. It was delivered to General Banks, according to his own statement, at 8 o’clock on the morning of the 9th of August, whilst his corps was still encamped two miles northwest of Culpeper. I was, in fact, his first order to move to the front. From the fact that neither General Banks nor his witnesses refer to any subsequent orders or instructions, they purposely leave the inference that he received no subsequent orders on the subject; and that from 8 o’clock in the morning until 6 o’clock in the afternoon of the 9th of August he received no orders from me concerning his operations. This omission on the part of General Banks is the more singular, because, aside from subsequent orders sent him on several occasions whilst he was on the field, in order to make sure that there would be no mistake about my orders and intentions, I subsequently (at 9 1/2 o’clock in the morning) sent Brigadier General Roberts, senior officer of my staff and an old army officer, to the field with full and precise orders to General Banks that he should take up a strong position near where Crawford’s brigade of his corps was posted, and if the enemy advanced upon him that he should push his skirmishers well to the front and attack the enemy with them, explaining fully that the object was to keep back the enemy until Sigel’s corps and Rickett’s division of McDowell’s corps could be concentrated and brought forward to his support. General Roberts was directed to remain with General Banks until further orders, and he accordingly did remain with him until I reached the field in person, just before dark, when Banks had been driven back to the position he took up in the morning.

General Roberts was authorized by me to give such orders to General Banks, or any other officer on the field, as were necessary to secure the execution of the plans and purposes above stated. I presume there was not an officer at my headquarters who did not know what my purpose was. In fact, the object was so plain that no military man could fail to see it. I conferred freely with General McDowell about it, and to his official report, published by the House of Representatives, I refer for a corroboration of my statement that that was the understanding of my purpose.

General Roberts, in obedience to the orders above specified, reported to General Banks early in the day on the 9th of August; gave him my orders, as above stated, and, in conjunction with him, selected the strong position he was to take and hold.

General Banks posted his corps accordingly, but during General Roberts’s absence, reconnoitring the extreme right of the position, General Banks began to move his corps forward; and when General Roberts returned he found General Banks moving forward with his whole corps to attack the enemy.

He immediately remonstrated against the movement, and some conversation between himself and General Banks ensued, Roberts protesting against the movement, and saying that the enemy was in heavy force—Banks replying that they were not in strong force, and that he could beat them and take their batteries; but at no time pretending even that he had orders from me to attack.

The above statement is a quotation almost verbatim from the testimony of General Roberts on the subject of the battle of Cedar mountain, delivered before the McDowell court of inquiry at Washington city in January, 1863. I transmit enclosed a certified copy of his testimony from the original record. The testimony taken by the McDowell court of inquiry has never been published, but it is on file in the War Department, and easily accessible to your committee, if it be necessary to verify the copy herewith enclosed.

Colonel L. H. Marshall, who is the officer said to have given General Banks the verbal order which he presents, is at present on duty as mustering and disbursing officer at Milwaukie, Wisconsin, and can readily appear before your committee. Brigadier General B. S. Roberts is still in service, and his station can be ascertained at the War Department. Captain J. McC. Bell, assistant adjutant general on General Roberts’s staff during the battle, is now on duty with me, and I wish him to be examined concerning the orders and despatches from me received by General Banks on the field during the 9th of August. Captain Bell was present when General Banks read these orders aloud to General Roberts. All my copies of these orders and despatches have been lost, but General Banks, doubtless, has the originals, the substance of which can be given by Captain Bell. They are all subsequent to the alleged verbal order given by Colonel Marshall in the morning.

The object in sending Banks’s corps to the front to take and hold a strong position against the advancing enemy, until Sigel’s corps and Rickett’s division of McDowell’s corps could be united in his rear, was so plain, and so clearly understood by every man of ordinary intelligence, that I find it impossible to believe that General Banks did not understand it.

It is clear to me, from his own reports at the time, that he did understand it. Although in easy communication with me all day, and although I received, at regular intervals, reports from him, he, on every occasion, expressed the belief that the enemy did not intend to attack him, and at no time intimated to me that he intended to attack the enemy. He neither asked or re-enforcements nor intimated that he needed them. His last report was dated at 4.50 p.m., and is as follows:

“AUGUST 9, 1862—4.50 p. m.

“To Colonel RUGGLES, Chief of Staff:

“About 4 o’clock shots were exchanged by the skirmishers. Artillery opened fire on both sides in a few minutes. One regiment of rebel infantry advancing now deployed as skirmishers. I have ordered a regiment from the right (William’s division) and one from the left (Augur’s) to advance on the left and in front.”

“5 p. m.—They are now approaching each other.”

This is the last despatch of General Banks, but before I received it I was half-way to the field with Rickett’s division, the rapid firing inducing me to believe that an engagement was going on. For General Banks’s despatches and my reasons for going to the front with Rickett’s division, see my official report and General McDowell’s in the volume printed by resolution of the House of Representatives.

I had not the slightest idea when I went forward that General Banks had moved from his position. He at no time stated to me his purpose to do so, and I supposed, of course, when I went forward, that the enemy had attacked him in the strong position he had been ordered to take up, and that he was still holding it. I presumed he would need help in defending that position, though he did not at any time say so, but constantly reported his belief that the enemy was not in force and would not attack.

I accordingly went to the front with Rickett’s division as a precaution, but when I arrived on the field I found to my surprise that General Banks had not only left the position in which he was posted in the morning, but had actually advanced two miles nearly in the belief that he could beat the enemy, as they were not in large force.

When near the field even I received word from Banks that he was “driving the enemy,” which information I at once communicated to Rickett’s division.

As I have stated in my official report, I never designed that Banks should attack the enemy before McDowell and Sigel joined him, and gave no order whatever to that effect. The whole weight of the facts and circumstances, the general understanding of everybody, and Banks’s own despatches, are against the fact that he himself, at the time, thought of understanding otherwise than that he was to hold his position against the enemy.

It is proper to state to your committee that on the 13th of August, three days after the battle of Cedar mountain, I sent a long telegraphic report of the battle to Major General Halleck, which was published in all the papers immediately, and which, as it was seen a day or two after its publication by most if not all the officers belonging to the army, must necessarily have been known to General Banks.

In fact, I am positive it was known to him, since I sent him a copy of General Halleck’s despatch acknowledging its receipt, and containing some remarks complimentary to the gallantry of General Banks and his corps. In that telegraphic report I stated precisely what is stated in my detailed official report, viz: that General Banks departed from his order by leaving the position he was ordered to take up and advancing to attack the enemy. I several times called upon General Banks, while he remained under my command, for a report of the battle of Cedar mountain, and when I was relieved from command of the army of Virginia, in September, 1862, the general-in-chief of the army, (Major General Halleck,) at my request, issued positive orders to General Banks, and one or two other corps commanders, to make reports to me immediately of the operations of their respective corps during the campaign of the army of Virginia, to be used in making up my own official report.

Yet up to this time not one word has been received from General Banks on the subject by me or by any other military official of the government. Now, at the end of more than two years, General Banks, being on leave of absence in Washington, procures the testimony of himself and one or two of his staff officers to be taken by your committee in relation to a verbal order, which he says he received from Colonel L. H. Marshall early in the morning of the battle of Cedar mountain, before his corps had even gone to the front. He seems to have interpreted this alleged order in the light of afterthought, without alluding to subsequent orders he received, and without notifying me or any other officer concerned in that battle that he intended to give or had given any testimony before your committee on the subject. Pure accident alone brought to my knowledge the fact that he had given such testimony, and enabled me, I trust in time, to present this paper and these facts as the basis of further examination of the subject, which I hereby respectfully solicit in the cause of justice and fair dealing.

I leave your committee to characterize such a transaction as it merits.

As General Banks, however, has chosen to pursue so questionable a course in this matter, it is but justice to the officers and men concerned, whether of his own or other corps of the army, that your committee examine thoroughly into the battle of Cedar mountain, and that for this purpose you procure the testimony of such of the division and brigade commanders of his corps and of other officers as are within reach.

I present the names of Major General Augur, Brigadier General A. S. Williams, Brigadier General George H. Gordon, Brigadier General Henry Prince, Brigadier General Geary, Brigadier General B. S. Roberts, Colonel L. H. Marshall, Captain J. McC. Bell, and such others as the official records show were with General Banks or under his command at that battle. I am much deceived and misinformed if their testimony does not exhibit the fact that, if even General Banks had received positive orders to attack, and had had every advantage on his side, his remarkable arrangements for that battle and his singular manner of making the attack did not render it next to certain that the result must necessarily have been defeat and disaster to his corps.

In my official reports I endeavored, as far as I possibly could, to avoid the censure justly chargeable upon General Banks for his management of that battle, though I was warned at the time by officers of high rank that it was misplaced generosity, and that my forbearance would assuredly be used against me thereafter. I did not then believe it possible, and felt disposed to deal with General Banks with the utmost tenderness, as I knew and sympathized with him in his mortification at the result of his previous encounter with Jackson, and perfectly understood his natural anxiety to avail himself of the first opportunity to retrieve his reputation. I was very unwilling under such circumstances to criticize his operations at Cedar mountain with any sort of harshness; but as he himself has chosen at this late day to reopen the question of the battle of Cedar mountain, by endeavoring to place on your records an ex parte statement of only one incident connected with it, it seems but proper that your honorable committee now examine thoroughly into it, in order that the whole subject may be fully and fairly presented to the country, and the measure of praise or censure be correctly fixed upon the parties concerned.

I am, sir, respectfully your obedient servant,

JOHN POPE,

Major General U. S. V.

Testimony of Brigadier General B. S. Roberts, U. S. V., concerning the battle of Cedar mountain, given before the McDowell court of inquiry.

WASHINGTON, D. C. January, 1863.

Brigadier General BENJAMIN S. ROBERTS, United States volunteers, a witness, was duly sworn.

By General McDowell:

Question. What was your position on General Pope’s staff in the late campaign in Virginia?

Answer. In the early part of the campaign I was chief of cavalry of that army; the latter part of it I was inspector general.

Question. What do you know of the orders of General Pope to General Banks relative to the battle of Cedar mountain, 9th day of August, 1862?

Answer. Early in the morning of the 9th day of August I was sent by General Pope to the front of the army with directions, when General Banks should reach a position where the night before I had posted General Crawford’s brigade, that I should show to General Banks positions for him to take, to hold the enemy in check, if he attempted to advance towards Culpeper. Two days previous, the 7th and 8th, I had been to the point; knew the country, and had reported to General Pope my impression that a large force of General Jackson would be at Cedar mountain, or near there, on the 9th, re enforcing Ewell’s troops, who were already there. General Pope authorized me, before going to the point, to give any orders in his name to any of the officers that might be in the field senior to me. I understood his object was to hold the enemy in check there that day, and not to attack until the other troops of his command should arrive and join General Banks.

Question. Was the battle of the 9th day of August at Cedar mountain brought on by the enemy or by General Banks?

Answer. In the early part of the day the battle was brought on (artillery battle) by the enemy’s batteries opening from new positions on General Crawford’s artillery. I had been directed by General Pope to send information to him hourly of what was going on, and I had expressed to General Banks my opinion, about three o’clock in the afternoon, that Jackson had arrived; the forces were very large. General Banks expressed a different opinion, saying that he thought he should attack the batteries before night. I stated to General Banks then my reasons for believing that an attack would be dangerous; that I was convinced that the batteries both on Cedar and Slaughter’s mountain were supported by heavy forces of infantry massed in the woods. He expressed a different opinion. He told me he believed he could carry the field. His men were in the best fighting condition, and that he should undertake it. I immediately sent a despatch to General Pope—I think my despatch was dated half past four—telling him that a general battle would be fought before night, and that it was of the utmost importance, in my opinion, that General McDowell’s corps, or that portion of it which was between Culpeper and the battle-field, should be at once sent to the field. Rickett’s division of General McDowell’s corps was in the immediate vicinity of the crossing of the road leading from Stephensburg with the road leading from Culpeper to the battle-field, or about two miles from Culpeper, and about five from the battle-field.

The court adjourned to meet to-morrow morning, January 9, 1863, at 11 o’clock a.m.

THIRTY-NINTH DAY.

Court-room, corner of 14th street and Penn. Av.

WASHINGTON, D. C., January 9, 1863.

The court met pursuant to adjournment. Present: Major General George Cadwalader, United States volunteers; Brigadier General John H. Martindale, United States volunteers; Brigadier General James H. Van Elen, United States volunteers; Lieutenant Colonel Louis H. Pelouze, assistant adjutant general, recorder of the court, and Major General McDowell, United States volunteers, and Brigadier General Benjamin S. Roberts, United States volunteers, the witness under examination.

* * * * * *

Brigadier General Benjamin S. Roberts, witness under examination, desired to state that, with reference to his testimony of the previous day, such portion of it as reads “General Pope authorized me, before going to the front, to give any orders in his name to any of the officers that might be in the field senior to me,” needs to be so qualified as to read that I was authorized to give any orders, so far as to carry out General Pope’s views, as had been expressed to me, (General Roberts,) in relation to holding the enemy there until his (General Pope’s) forces could come up.

By General McDowell:

Question. If General Banks had not attacked General Jackson in force on the 9th, do you think Jackson would have attacked Banks?

Answer. I do not think Jackson would have attacked Banks in a position where he was first posted on coming on to the field. The position was exceedingly strong, and one which a small force like General Banks’s could have held against a larger one of the enemy. General Jackson’s troops had made a long march that day, and I do not think they were in a condition to attack General Banks.

Question. Is the witness to be understood that General Banks fought the battle on his own responsibility, and against witness’s advice, and the known expectation of General Pope?

Answer. When General Banks first came on to the field I met him, and went to the front with him, showing him positions where the enemy had batteries already posted, and where I had discovered they were posting new batteries, and showed General Banks the positions where his own corps could take position to advantage, and hold those positions, as I thought, if attacked. I then told him that General Pope wanted him to hold the enemy in check there until Sigel’s forces could be brought up, which were expected that day, and all his other forces united to fight Jackson’s forces. I mean to be understood to say that it is my impression that General Banks fought the battle entirely upon his own responsibility, and against the expectations of General Pope, and those expectations had been expressed to General Banks as I have already stated, perhaps more strongly.

Question. Do you know why General Banks advanced to make a division movement upon the enemy on the 9th of August without the aid of General McDowell’s troops? If so, state why.

Answer. I can only state impressions from facts which I can relate. General Banks had seen nothing of the enemy on that day, or not much of the enemy, as the country was such (and well known to them) as to enable them to conceal their movements from General Banks. After he first came on to the field and I had suggested positions to the left of Crawford’s brigade, where his main force should take position, he proceeded to put those forces in position in support of Crawford, and on his left. I went to the extreme right with one of his brigades (Gordon’s) to put it into position, and was gone an hour or more, I should think, as I went some distance to the right, under the belief that a part of the enemy’s forces were endeavoring to turn that flank. On returning back to the field I found General Banks had advanced his lines in order of battle, considerably toward the enemy, so that very sharp musketry firing had already commenced. I then expressed to General Banks my convictions—and I think this was about three and a half o’clock—that the enemy was in very large force, and massed in the woods on his right.

General Banks replied that he did not believe the enemy was in any considerable force yet, and said he had resolved to attack their batteries, or to attack their main force. It was either one or the other. From this state of facts I am convinced that General Banks made the attack in the belief that the enemy was not in large force, and that he would succeed in his attack without the aid of other troops.

Another reason for this belief is that General Banks supposed that his own force was between twelve and thirteen thousand, whereas it was three thousand less than that number. He was led to this belief by some mistake in returns, which he did not discover until after the battle was fought.

The court adjourned to meet to-morrow, January 10, 1863 at 11 o’clock a.m.

L. H. PELOUZE,

Lieutenant Colonel and Recorder.

A true copy of the record.

W. H. W. KREBS,

Captain and A. D. C.

A true copy,

JAMES McC. BELL,

Captain and A. A. General.

Milwaukie, Wisconsin, December 26, 1864.

GENERAL: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your note calling my attention to an order which General Banks states that I delivered to him verbally.

General Banks states that I ordered him to leave the strong position he was ordered to take up, and advance and attack the enemy.

The order received from you and delivered by me to General Banks, about eight o’clock on the morning of the 9th of August, before he moved from Culpeper to the front, was, to the best of my recollection, as follows:

“GENERAL: The general commanding directs that you move to the front and take up a strong position near the position held by General Crawford’s brigade; that you will not attack the enemy unless it becomes evident the enemy will attack you; then, in order to hold the advantage of being the attacking party, you will attack with your skirmishers thrown well to the front.”

The above is the exact language used by me to General Banks as near as I can remember; my understanding of your intention was, that you wished to hold the enemy in check, and put off a general engagement until Sigel’s and McDowell’s corps could be got up, and I think that such was the understanding of every one in the army.

My understanding of your order was, that General Banks was to attack with his skirmishers, and my intention was for him so to understand the order.

I am, general, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

L. H. MARSHALL,

Colonel and A. A. D. C.