The following review of the 21st Virginia Infantry’s first year of battle was prepared by FCMB board member Bradley Forbush. This review was prepared in conjunction with a tour of Cedar Mountain in August 2018 by Mike Dove, a descendant of five 21st Virginia Infantry members (read the tour report).

The 21st Virginia Volunteer Infantry was organized in July 1861 at Richmond. The regiment spent a couple of weeks training in Richmond before it was ordered to the Allegheny mountains of Western Virginia. At 11 a.m. on July 18, 1861, the newly minted soldiers, 850 strong, boarded a slow train to Staunton, on the Virginia Central Railway, and arrived early the next morning. From Staunton they proceeded westward on foot, arriving July 26 at Huntersville where they joined Brigadier General W. W. Loring’s command. #1

Loring’s army was then battling Federal troops for control of the mountain roads and passes that led east to Staunton and the Shenandoah Valley. They had recently lost ground to the increasing number of Federals in the region. The 21st Infantry was part of the badly needed reienforcements hurried forward to help out.

Unfortunately, the 21st would not provide much aid in the coming campaign. As soon as they arrived a measles epidemic broke out in camp effecting 75 percent of the men. By August 6 only 25 percent of the men were fit for duty. Those that were well enough helped clear land and build roads for the impending military operations.

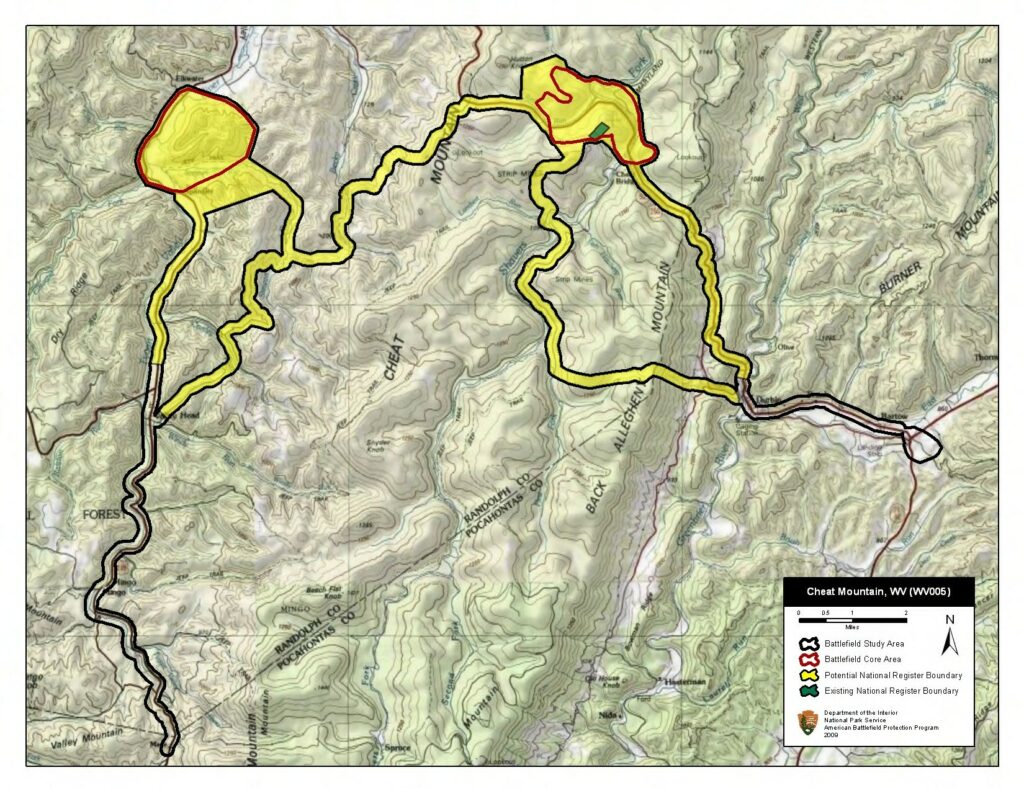

The poor condition of the men caused the 21st Virginia to be assigned a lesser role in the Cheat Mountain Campaign, September 12 -15, 1861.

The Cheat Mountain Campaign

To defeat the Federals, General Robert E. Lee and General W. W. Loring devised a complicated plan for 5 Confederate columns to simultaneously attack two strong Union Forts, 8 miles distant by bridle path over the mountains, but 15 miles distant by road. Three columns attempted to assault the Federals at their Cheat Mountain fort, while 2 columns waited to attack the Federal stronghold at Elkwater. The debilitated 21st Virginia was held in reserve guarding a road far from the intended action.

Rain, fog, bad roads, and poor communication between the columns doomed the campaign. The lead column was repulsed before its assault on Cheat Mountain fairly began, and the entire affair was called off. It was a fiasco for General Lee. The army returned to their camps at Valley Mountain, while General Lee tried to formulate another plan. He left the area on September 24.

The soldiers of the 21st Virginia remembered him fondly as a kind and fair leader during this time, and the regiment could later boast about being among the earliest troops commanded by the future great general.

The 21st Virginia continued picketing different mountain roads in this region until early December 1861. Their next assignment was with General “Stonewall” Jackson at Winchester, and what was to become the brutal Romney Campaign.

Hancock and Romney Campaign

The already legendary “Stonewall” Jackson was anxiously awaiting reinforcements for which he had been pestering authorities at Richmond ever since he received command of the Shenandoah Valley in November 1861. He planned an assault on the Federal Garrison in the Allegheny Mountains at Romney, VA, 43 miles west of Winchester. General W. W. Loring reluctantly agreed to reinforce Jackson and began slowly shuffling his command to Winchester from Staunton in early December.

The 21st Virginia reached Winchester on December 27 after a slow and exhausting sixteen day march. They were the last of General Loring’s men to arrive. That evening, Brigade Commander, Colonel William Gilham, a friend of Jackson’s, paid him a visit, and brought along Lieutenant Colonel John M. Patton, then commanding the 21st Virginia.

Patton explained to Jackson, “Both my regiment and myself are ready to execute your orders, but I feel it is my duty to say to you that my men are so foot sore and weary that they could just crawl up barely and if they have any double-quicking to do from the character of your orders, I suppose they will.”

Jackson replied, “Colonel, if that is the condition of your men, I will not send them on this expedition. Take them back and report to your brigadier.” Patton quickly back-tracked his opinion in front of Jackson but his comment reveals something of the health of his men. #2

The truth is, the troops in General Loring’s command were not ready for the hardships of a winter campaign.

The March to Hancock

The first march of the campaign got off to a balmy start on an unseasonably warm New Year’s Day, 1862, causing many inexperienced soldiers to leave their tents and overcoats behind for the supply wagons to carry. In the afternoon the weather changed. The temperature dropped and the wind kicked up. It turned very cold. Men without coats or blankets tried to sleep at night out in the open on frozen ground. The supply wagons would not get up for another full day. The second day’s march was worse, continuing in a snow storm in “bone-numbing cold” without food or proper clothing,

Snow and cold crippled Jackson’s force during this campaign yet he pushed the men hard, ever onward. By January 6, Jackson had accomplished his first strategic objective. He drove Federal pickets out of Bath Hot Springs and across the Potomac River to Hancock, Maryland. The Federals reacted quickly and sent reinforcements to Hancock forcing Jackson to abandon plans to take the town. But, with his rear guard now cleared of Federal troops, he turned his attention to his main objective; capturing the town Romney.

On January 7, he marched his troops south. To quote Jackson’s biographer James I. Robertson, this was the worst day of the campaign: “The region was in the throes of a major snowstorm.” Henry Kyd-Douglas of the 2nd Virginia wrote in a letter after the campaign, “The road was an uninterrupted sheet of ice … 3 men in our Brigade broke their arms by falling, several rendered their guns useless. Several horses were killed & many wagons were compelled to go into night quarters along the road, being unable to get along at all.” #3 The army camped at Unger’s Store for 4 days to put winter shoes on the surviving horses. About one third of the troops were sick or disabled.

The four day delay frustrated Jackson who was impatiently waiting to proceed, when suddenly, Confederate scouts returned to his camp with the astonishing news that Federal troops had abandoned Romney. The town was open for the taking.

Learning this, Jackson quickly moved to occupy Romney on January 14. He posted Loring’s troops there as a guard, and returned to Winchester with the Stonewall Brigade, January 23, satisfied he had obtained a strategic victory. But the officers and men of General Loring’s force saw things differently. Feeling vulnerable to Federal attack at Romney, influential officers of Loring’s command petitioned authorities at Richmond to order a return to Winchester. Their request was granted. Jackson was ordered, unwillingly, to bring Loring’s command back to Winchester in early February. The campaign had a devastating effect on morale. John Worsham of the 21st Virginia summed up the regiment’s experience in these words:

“We reached Winchester on the [Feb] 6th, and went into camp, after being away a little over a month, undergoing the most terrible experience during the war. Many men were frozen to death, others frozen so badly they never recovered, and the rheumatism contracted by many was never gotten rid of. Many of the men were incapacitated for service, large numbers were barefooted, having burned their shoes while trying to warm their feet at the fires.” #4

About 1,500 men out of 8,500 total were sick in hospitals around Winchester and surrounding towns as a result of the Romney campaign.

The Valley Campaign; Battle of Kernstown March 23, 1862

Union General N. P. Banks crossed the Potomac River into the Shenandoah Valley March 1, 1862, and proceeded to slowly move up the valley to clear it of Confederate troops. General Jackson had been reluctant to abandon the town of Winchester to the approaching enemy, but his small command was no match for the number of advancing Federals. He vacated the town on March 11. Ten days later, he learned a large part of General Banks’ army was leaving the Shenandoah Valley for Manassas. Jackson decided to strike.

The battle of Kernstown was a Confederate defeat, but it was the first stand up fight for the soldiers of the 21st Virginia and they did well. During the engagement they rushed to the aid of the 27th Virginia “and restored their broken line.” #5 It was also the first time many of them saw a man struck by an enemy shell. John Worsham wrote:

“A gun or two of the Rockbridge battery now joined us, we marched under a hill, and they to the right on top of the ridge. These guns were occasionally in their march exposed to the view of the enemy’s battery, and they fired at them, the shells passing over our regiment. One of them struck one of the drivers of the guns, tearing his leg to pieces, and going through the horse. Both fell; the shell descended and passed through our ranks and struck a stump not far off, spinning around like a top, and before it stopped one of the company ran and jumped on it, taking it up and carrying it along as a trophy. This is the first man of the war I saw struck by a shell; it was witnessed by the majority of the regiment.” #6

After the defeat at Kernstown, the eccentric general Jackson led his small force 100 miles up the valley in a slow fighting retreat, seeking to confront the enemy at any given opportunity. John Worsham described it this way:

“This was the boldest retreat I ever saw. General Jackson was defeated at Kernstown on the 25th of March by an overwhelming force, and the next day retired up the valley more slowly than I ever saw him march; and when we went into camp at night we tarried as long as possible. If the enemy did not hunt for us, General Jackson would hunt for them The regiments had orders to drill just as if no enemy was within a hundred miles of us. It can be seen that our movements were slow since it took us from March 24 to April 18 to march about one hundred miles, although we marched about half that distance in two days when we advanced to Kernstown.” #7

During the course of this famous campaign General Jackson sequentially defeated 3 independent Union commands and drove the Federals out of the Shenandoah Valley.

The campaign consisted of a series of stealth marches and surprise attacks that caught his enemies off guard.

Battle of McDowell, May 8, 1862

On April 30, General Ewell’s force of 8,500 men joined Jackson’s force, more than doubling his army. Jackson felt he still needed more troops than he had available to clear the valley of Federals. Meanwhile, Brigadier General Edward Johnson in the Allegheny mountains west of Staunton was pleading with Jackson to come help him confront General John C. Fremont’s advancing army. Leaving Ewell to watch Union General N.P. Banks to the north, Jackson marched his command west to Staunton, and then into the Allegheny Mountains (more than 100 miles) to help Johnson. Jackson and Johnson encountered the vanguard of Fremont’s army at the hamlet of McDowell on May 8, repulsed their repeated attacks, and forced the ill- equipped Northerners to retreat. Once again the 21st Virginia were fighting in the Allegheny mountains about 45 miles distant, by way of winding roads, from their initial camp at Huntersville.

Jackson’s force chased the retreating Federals into the mountains for a few days but when satisfied they were no longer a threat he turned his attentions back to the more urgent task of defeating General Banks. Success in the Allegheny’s added General Johnson’s 3,000 men to his command. These troops would suffice for the reinforcements he needed to confront Banks in the Shenandoah Valley. Now General Jackson needed to quickly re-unite with General Ewell before the latter general’s force might be called away. In order to make good time, Jackson issued a strict marching regimen to his troops so they could cover 15 — 20 miles a day, under the most difficult of conditions. With little or no food, they marched over horrible mountain roads during a 5 day period of torrential rain, May 12-17, and covered the 67 miles they needed to reach the vicinity of Harrisonburg. The troops began to refer to themselves as Jackson’s Foot Cavalry.

On May 18, near Harrisonburg, Generals Jackson and Ewell met, and planned their next move. On May 19 the new military offensive began. The first objective was to defeat the Union garrison at Front Royal.

Again we turn to the pages of John Worsham’s memoir. He wrote, “On May 21st Jackson marched down the Valley pike. When we reached New Market we took the road leading to the Luray valley, and formed a junction on the 22d, near Luray, with the balance of General Ewell’s command… Jackson now had the largest army he had ever had. He had brought Gen. Edward Johnson’s force of six regiments and some artillery with him from the Shenandoah mountain, and had Ewell’s command, and his old command.

“On the 23d Jackson’s army left its bivouac near Luray, taking the road to Front Royal, the head of the column arriving about three or four o’clock in the afternoon. General Jackson as usual, made an immediate attack on the enemy, with the few men who were up. His eagerness all through this campaign was surprising, and his escape from death was almost a miracle.” #8 Front Royal was captured, although the 21st Virginia was not engaged there.

One of the more grueling marches for the regiment came the next day on May 24 and 25 as Jackson attempted for a second time to retake Winchester. The 21st Virginia suffered through an especially difficult 7 mile march from Cedarville to Middletown, followed by a forced night march to Winchester with only 2 hours rest.

Col. John Patton of the 21st Virginia reported, “As the men limped along with weary limbs and feet throbbing with pain, on what seemed to them an aimless march, I heard them denouncing Jackson in unmeasured terms to ‘marching them to death for no good.’ It was my duty no doubt to have rebuked these manifestations of insubordination, but, feeling that their sufferings in some measure condoned their offense, I took no notice of the breach of discipline.” #9

Battle of Winchester, May 23, 1862

The 21st VA supported the Rockbridge artillery during the attack on Winchester. They were under fire from enemy shells but lost no men during the engagement. General Banks men put up a heavy resistance with artillery fire, but before long, the Union line was outflanked and driven north through the town. Banks’ force continued retreating north, 35 miles to the Potomac river, which he crossed into Maryland.

Jackson’s continuing success caused many to forgive him the hard service they endured. John Worsham wrote, “Jackson lost a very small number of men, but he had led us for three weeks as hard as men could march. In an order issued to his troops the next day, he thanked us for our conduct, and referred us to the result of the campaign as justification for our marching so hard. Every man was satisfied with his apology; to accomplish so much with so little loss, we would march six months! The reception at Winchester was worth a whole lifetime of service.”#10

Three days after the battle of Winchester, the 21st Virginia was detached from Jackson’s main body to guard the large number of captured Union prisoners, estimated to be about 2,300 men. The regiment numbered only 250 men at this time. This is down from 600 men tallied in a report dated April 18. One factor that contributed to the drop in numbers was the muster out of Company B, the Maryland company. Its one year term enlistment expired during the Winchester campaign. Going forward, the regiment had only 9 companies.

Anxiety that the prisoners might escape was ever-present during Jackson’s hurried retreat up the valley from May 31 to June 5. The wagon train led the march. The prisoner escort followed. Once again, a pelting hard rain daily encumbered the move. The roads were muddy. Union Generals Fremont and Shields were threatening to close in and cut off the small Confederate army’s retreat. Things got a little dicey for a while around the village of Port Republic on June 6, but the 21st Regiment made the long journey with their captives, across the mountains, from the Shenandoah Valley to Lynchburg without serious incident. They marched beyond Waynesboro, to just south of Charlottesville where prisoners and escort boarded cars at the North Garden Depot of the Orange & Alexandria railroad, and made the last stretch of the journey by train. At the Lynchburg Fairgrounds, the Federal prisoners were turned over to the care of the City Guards. The 21st Virginia returned by rail to Charlottesville where they reunited with the rest of their brigade and General Jackson’s army on June 21 and proceeded with them to Richmond.

Battle of Gaines Mill

The regiment did well in Richmond, participating in newly appointed Commanding General Robert E. Lee’s largest attack of the war at Gaines Mill, June 27, 1862. They came out of the 7 days fighting around Richmond with only 1 man reported wounded. That luck would be absent at their next engagement: Cedar Mountain on August 9, 1862.

NOTES

- John Worsham. One of Jackson’s Foot Cavalry, Neale Publishing Company, New York, 1912. p. 37.

- James I. Robertson, Jr. Stonewall Jackson. Macmillan Publishing USA, New York, 1997. p. 302.

- Robertson, p. 309. Footnote: Kydd-Douglass to Tippie Boteler, Jan. 12, 1862, Boteler Papers.

- Worsham,p. 63.

- Robertson, p. 342.

- Worsham, p. 67.

- Worsham, p. 74.

- Worsham, p. 82.

- Robertson, p. 401. Southern Historical Society Papers, 8 (1880): 141.

- Worsham, p. 88.

Print This Post

Print This Post