This is the fourth and last post in a series on the service of Captain Erwin Ambrose Bowen of the 28th New York Volunteers and the 151st New York Volunteers. We are grateful to Mary Z. Robinson for sharing her ancestor’s story with us.

Introduction

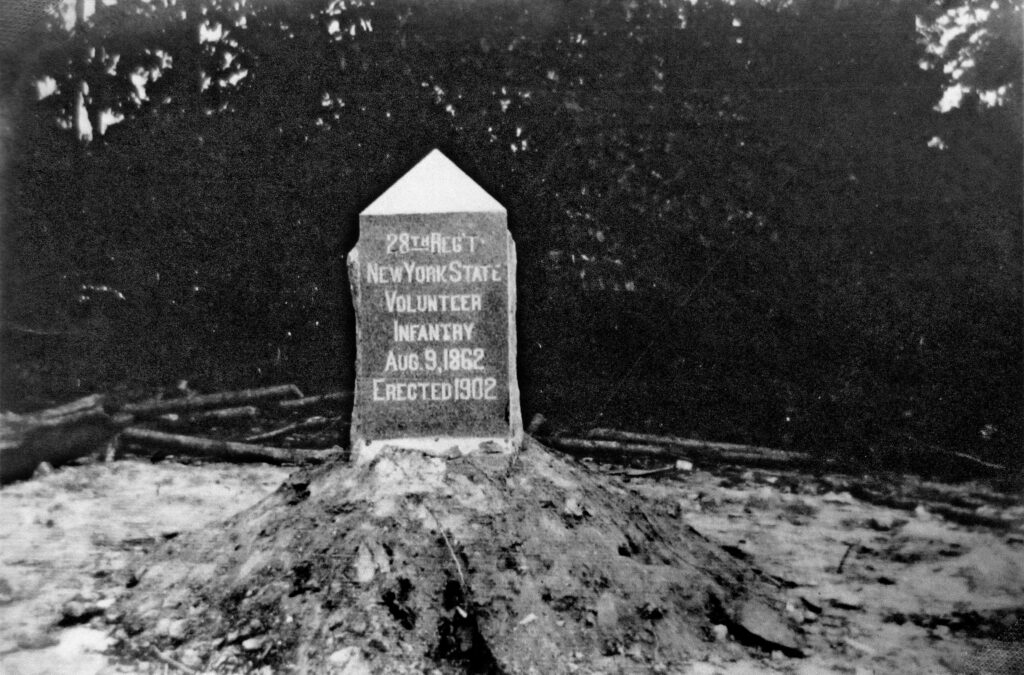

Presented here is the narrative of Harry Bowen, the youngest son of Captain Erwin Bowen, Co. D, 28th New York Volunteers. Harry attended the 1902 40th reunion of the regiment at Culpeper, VA, and the dedication of the 28th NY monument in the Culpeper National Cemetery. This document was in the collection of Lon Lacy, received from Capt. Bowen’s descendant, Mary Z. Robinson, in 2012 at the 150th anniversary of the battle.

Erwin Ambrose Bowen died of typhoid pneumonia on January 22, 1889. The hometown newspaper the Medina Tribune reported:

“He passed bravely and unflinchingly … conversed freely, arranging every detail of his business and domestic affairs, and bid each and all good-bye. He was conscious until the last and death came quickly and apparently without struggle.”

Nearly a dozen eulogies were printed in papers near and far mourning the loss of this brave soldier and stalwart friend.

Thirteen years later, in August 1902, his youngest son Harry Bowen traveled to Culpeper, Virginia to attend the dedication of the 28th New York Volunteers monument in the National Cemetery located there. He met many of his father’s old comrades from the 28th, and many of the Virginians who opposed the 28th at the Battle of Cedar Mountain. They too, came to honor their former foes.

In the narrative Harry makes references to his father & sister’s prior visits to Virginia. The 28th NY Vols. initiated the first Blue/Gray reunions of the post-war period. Nothing of the kind had previously been attempted. In 1882, Col. Edwin F. Brown discovered the regiment’s lost colors in the flag-room of the War Department, Washington, D.C., among a collection of returned flags discovered in Richmond at the end of the war. He at once wrote to the Secretary of War requesting the colors be returned to the regiment and its surviving members. It was thought that the Virginians might be induced to unite with the regiment in the ceremonies of the return of the flag, and to be the guests of the 28th for the occasion, to meet as brothers and friends, when they had only met before as enemies in battle. On May 21 & 22, 1883 at Niagara Falls in New York, 153 Virginians from the Shenandoah Valley attended, with the majority, 83 in number, being veterans of the 5th Virginia. The Virginians reciprocated and on May 22, 1884, 100 veterans of the 28th New York Volunteers, accompanied by their families, traveled to the Shenandoah Valley and were hosted by veterans of the 5th Virginia Infantry at Staunton.#1

When Harry Bowen traveled to Culpeper in 1902, he brought a new camera along with him. But either it was a very poor camera, or he was a very poor photographer. I edited these images which accompany the journal, in Photoshop, in hopes of revealing a bit more detail. I succeeded with a couple of them. Poor as they are, the images Harry captured provide an incomparable time-capsule record of the event. When he returned home, Harry typed up a memoir of his experiences to share with other family members.

This memoir was given to me by the late Lon Lacy, of our own Friends of Cedar Mountain Battlefield. Lon was a meticulous researcher. Through other documents that came with the manuscript I was able to reach out and contact Mary Z. Robinson, a direct descendant of Erwin Bowen. She assisted me in editing the journal and provided me with many more details of her ancestor’s military history, which I have posted on this website in parts 1 – 3.

- Capt. Erwin Ambrose Bowen, 28th NY; Part 1: Introduction

- Capt. Erwin A. Bowen, Part 2; Libby Prison

- Capt. E. A. Bowen, Part 3; With the 151st NY at Payne’s Farm

Without further ado, here is Harry Bowen’s memoir.

Note: This narrative is written in the language of its time.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1862 – 1902.

Culpeper —

—Cedar Mountain

In Memory of Father

Ever since I have been old enough to remember, I have had a desire to visit that part of Virginia which was the scene of father’s war experience. The mere mention of the names of Harrisonburg, Culpepper, and Harpers Ferry has sent a thrill though me, and brought to mind pictures which were formed years ago from the stories father used to tell us. I suppose, being younger than the rest of the children I have had a different or more romantic impression; a fairy tale with father as the hero.

When I first heard of the reunion at Culpepper I decided to go if possible, and on the morning of the eighth of August I left home in Catonsville in time to meet the Niagara Express at union station, Baltimore.

On the way I bought the Baltimore Sun and was surprised to find a good account of the battle of Slaughter’s Mountain or Cedar Run as the Southerners call it, as well as an editorial on the reunion of both the Blue and the Gray, on the scene of the struggle. I later brought the article to Mr. Boyce’s attention and it is to be printed in the report, I believe.

You may be sure I lost no time in going through the train in hopes of seeing some one whom I knew, but in this I was disappointed. Thinking, however, that I might have missed at least one, I went through again, but with the same result. I sat down in the seat with a man who looked as though he might be an old soldier, and so he was, but not of Co. “D”, or even the 28th Regiment. After talking a short time I decided to make another trip through the train, and having satisfied myself that all were strangers to me, I made up my mind that it was time that some of those people, with 28th badges on their coats knew that I wanted to be on speaking terms, so I asked the next man if he could direct me to Mr. Boyce. He said that he could; he would, and he did. I introduced myself as Col. Bowen’s son, and was very cordially received. Mr. Boyce and party occupied the middle section of the Buffalo sleeper, and after meeting Mrs. Boyce, her sister, and Mrs. Stillson, — the latter the daughter of Adj. Sprout who was killed at Cedar Mountain — I passed the remainder of the trip to Washington with them. Mr. and Mrs. Boyce asked after Mother and the family and we had a very pleasant chat. I assisted the ladies to National Hotel which is half a block from the station, on Pennsylvania Avenue.

The Southern Railway had arranged to run a special train to Culpepper, if there were one hundred or more people; but as there were less than fifty, we had to wait for the regular train at 11.15 A.M. This was an express train which was not scheduled to stop at Culpepper but owing to the number of people this arrangement was made. We did not stop between Washington and Culpepper, a distance of sixty seven miles, you will see that we were probably better off than we would have been on a special. Those who wished breakfast went to the dining room as soon as we arrived at the hotel in Washington. Afterwards the men collected in the office and lounging room of the hotel. I struck up a conversation with a man who was sitting with a party of four or five others, but as he was not a Co. “D” man, I do not remember his name. A man sitting in the group said, “Are you Col. Brown’s son”? “No, sir,” I replied, Col. Bowen’s. — Capt. Bowen, Co. D.” He arose, held out his hand and said, “Sergeant Baker, Company D.” Another man said, “Why, are you Erwin Bowen’s son? I am glad to see you. My name is Newbury. I helped your father in drilling Co. D.” We had a good chat, and you may believe it was very interesting to me. In fact, the unexpected, romantic way in which I met so many of father’s old army friends and associates, is one of the pleasant remembrances of my trip.

In due course of time we were on the train for Culpepper. Co. D. was well represented, and in fact half of the number were of that company. I soon found myself sitting on the arm of a seat listening to a discussion of the battle. There were four or five men in one group, among whom were Sergeant Baker, Lieut. Seeley and Mr. White all of Co. D. Mr Seeley was positive that he could tell the exact position of the Regiment; the charge across the wheatfield, and the general lay of the ground at the time of the battle. He was the most interesting talker I met; had a way of making one feel he knew what he was talking about, whether he did or not, and I believe had the best idea of the ground, and located the exact positions better than any one else. I said: “I do not understand how you men can remember and be so positive about things which happened forty years ago.” “Why, Seeley replied, “I’ll tell you why, I can recite for you line for line, pieces which I learned in school when a boy. But things which I learned ten years ago I do not remember. Now I can find the spot where the Company came out of the woods and charged across the wheatfield, broke down, or climbed over the fence and went into the woods on the other side, and I have not seen it in forty years.”

There was some argument about the distance across the wheatfield to the fence. It seems that the woods have been cut back, and from that fact it was thought that it would be more difficult to locate old landmarks. Each man had his own experience to relate and it was all very interesting to me.

Just before we reached Culpepper I sat down in a seat with a man, or rather opposite a man in a double seat. He leaned forward and said: “I understand that your are Col. Bowen’s son.” I said that I was, and he replied: “My name is Roberts.” I told him, mother had written that he would be there, and I said that I was glad to see him, and would like to meet Mrs. Roberts, which I did before we left the train. Mr. Roberts was not in the battle, but as he holds the record for attendance at the reunions of the Regiment, did not of course wish to miss such an important one.

We arrived at Culpepper about half past one. I helped the ladies of the Boyce party to the nearest hotel which is just across the street from the station, and in fact the tracks run directly in front of the door. Mr. Boyce later decided to go to another, or rather the other hotel, which was farther from the noise of the trains, but this advantage was counterbalanced by the poorness of the table. I, as most of the men I was interested in, stayed at the hotel nearest the tracks, although when I found that I was down for a cot in a room with several others, I tried the other place. Finding that I could do no better, I came back and secured one of the three beds and two cots in a nice large room on the second floor. After dinner, which by the way was a good one, it was time to go to the cemetery, where the monument was to be dedicated. I was nearly there when I remembered that I had left my camera at the hotel, but as the distance was not great, I soon returned with it and snapped the entrance to the cemetery as my first picture.

The monument is a simple, straight shaft standing to the left of the entrance drive, and near the center of the grounds. The stand erected for the exercises was draped with the battle flags of the 28th.

Some time was taken up in reading reports and the regular business meeting, after which the men were grouped around the monument, where the local photographer was ready to take their pictures. I took this opportunity to take a picture of the old flag, and then had plenty of time to snap the group in front of the monument.

The regular exercises were interesting. Col. Brown’s son paid a tribute to his father in his oration. Mrs. Stilson was introduced to the audience as the daughter of Adj. Sprout, being three months old at the time of his death at Cedar Mountain. Her father had wished her named Annie Laurie Sprout, which lent an added charm to the song of Annie Lourie, which she sang. The enthusiasm brought her back the second time, and all joined in the Star Spangled Banner.

Col. Brown made a short speech, but his voice was so weak, that although I was not over twenty feet away, I could hear very little. I did manage to hear him say, however, that he had not seen so large an audience before without several camera friends, but so far he had not seen any. I immediately proceeded to show him one, and snapped the camera before he had time to turn his head. Mr. Boyce said, “There is Col. Bowen’s —”, but either he did not add the “son”, or it was lost in the laugh which followed. I am very sorry that this picture was a failure, but it made a little fun at the time at all events.

The most interesting part of the program to me was Gen. King’s poem, which he read with a great deal of expression, and in fact the life which he put into the words was the charm of the thing.

After the exercises people closed around Col. Brown, and when there was a chance I went up and said, “Col. Brown I am Col. Bowen’s son, Capt. Bowen, Company D.” — “Why, are you Erwin Bowen’s son! there is no man I would rather see here today than Erwin Bowen.” He asked after the family and said he wanted me to meet his son. He was glad to see me and said, “Well, how did you happen to be here?” I replied, “You could not keep me away, Colonel.” He patted me on the arm, and about fourteen people more or less tried to speak to him so I left. The Colonel is eighty years old and looks it! [He] has a young physician with him all of the time. The exercises and the reunion must have been a great strain on him. I doubt if he will be strong enough to attend another if he lives.

On arriving at the hotel, — but you old Northerners don’t know what a southern hotel in a small town is like. Culpepper has a population of about two thousand; is only sixty-seven miles from Washington on the Southern Railroad. Such a town in New York state would probably have electric lights, but certainly gas and running water in its best hotel. Not so in Virginia, or at least in Culpepper. Coal oil and a pitcher answered the purpose, and bring about the same results.

The supper was also truly southern, and I have no objection to moving down there in time for that meal, — but this is what we had: fried chicken, creamed potatoes, hot rolls, milk, honey and peaches. I have heard of Virginia fried chicken, and can recommend it to any one, as a recompense for the lack of some things which are not to be found there. I do not remember father’s being impressed with the quality of Virginia fried chicken, to say nothing of the quantity. In fact, all of the men assure me that the reception given them forty years ago was warm, but not quite so cordial as upon this occasion, when there was certainly every evidence of good feelings.

After large quantities of the above mentioned good things were disposed of, to the satisfaction of all save possibly the hotel man, we all collected on the front verandah which ran across the front of the house and around the left side. It can hardly be called a verandah because it was only raised three or four inches from the board platform which extended beyond to the tracks.

I sat in a group with Messrs. Seeley, Baker, Newbury and Roberts listening to the arguments and exchange of experiences. After the exercises in the afternoon I heard Col. Williams of the 5th Virginia Infantry, — which as you will remember was the regiment which turned the 28th’s flank, — tell of the movements of his command. Seeley was in the group and told of the 28th’s charge. He said, “At the order to charge we started across the wheat field dragging our guns; climbed over or broke down the fence, and went into the woods beyond. I went over to the left, and before I knew it was separated from the rest of the Regiment, and found myself with a squad of an Illinois Regiment. [probably 3d WI? or 27 IN?—B.F.] When the order to charge was given we thought we were to try to take a Battery, which was at the edge of a piece of woods over to our left. I saw an officer of on a horse trying to rally his men, when all at once he pitched forward probably instantly killed. [This is Lt. Col. Ruger, 3d WI] Someone called out, “Boys we had better get out of this.”

I said, “get out, h—, we’ve got ’um licked” but I soon found that we hadn’t, and started back through the woods only to run into your (Col. Williams’) men of course. So I started to go ‘round, — only I didn’t go far enough. I met some fellows over that way, and they seemed real anxious that I should stop and talk with them. I didn’t want to at first, but they sort of insisted so I thought maybe I’d better. Well sir, them fellows was real nice to me, invited me to go down to Richmond with ‘em. I told ‘em, me and a lot of fellows from up our way, had intended going down to Richmond, and had started several times, but we was hindered by one thing an’ another, — well, I could see they was going to feel put out if I didn’t go long with ‘em, so I went and stayed a spell at the hotel Libby, and after I got sort of tired of the victuals there, I went over to the hotel Belle Isle for a time, and then I got sort of homesick, and told the folks that had charge of the place, that I thought I’d come home.”

The campfire at the opera house was to begin at eight o’clock, so about a quarter of the hour Mr. Roberts and myself started so that we would have no trouble in getting a seat. We were particularly successful as we had every chair in the house to choose from.

I had anticipated a great deal of pleasure from this meeting; had expected to hear anecdotes from the men touching on the camp at Culpepper; the march to the battlefield; the camp; the night before the battle when the men were together for the last time in months; and so many were never to be with them again. I had looked forward to this part of the reunion with the most interest, save possibly being on the battlefield; and although it was very interesting, I was disappointed to find the entire evening taken up by a few men, who for the most part talked well; but did not take part in the battle or have a personal knowledge of the Regiment.

The speakers were called from the audience and introduced very informally by Judge Grimsley of Culpepper. Major Grimsley welcomed the friends and veterans of both Blue and Gray, and spoke of the pleasure all felt in meeting as friends and citizens of one great united country. He said that he was a confederate soldier, or rather a member of the Cavalry, — as the Infantry never considered them as soldiers and he was proud of it. No man could go through such a war without having the greatest respect for those who fought against him. He said, “We of the South were just as honest in our convictions as you of the North; though we are now as glad as you that the matter was settled as it was. The decision had to come, and I am glad that we can leave a united country to our children.” I often wondered, said Maj. Grimsley, “when in our camp, what you were doing in yours; whether you had the good times, and sang the songs which we did. But sometimes when riding on picket duty at night, and the smell of the boiling coffee was brought to me on the cold night air, I thought that perhaps you had better times than we did.

The Mayor of Culpepper delivered the address of welcome. Judge Grimsley said “I have the pleasure of introducing, etc.. at which the mayor, a beardless youth — (due partly to the use of the razor) — arose to be presented. After waiting several minutes in which “he stood a spell on one foot first, then stood a spell on tother. And on which one he felt the worst, he couldn’t ha’ told you ‘nuther”, — it was evident that the Mayor had forgotten all about him. However, in due course of time he was let loose. We were carried from Marathon to Thermopylae on the one hand; Waterloo on the other and fell from both at Cedar Mountain. It was something like a phonograph rattling off the words of a Daniel Webster, aided by Prof. Pindar who pulled the wire, which regulates first one and then the other arm. It is a difficult if not impossible thing for one who has neither the voice or ease of manner and gesture to deliver an oration; so I do not wish to seem to criticize the gentleman who for the time being was the host of the Regiment. Still if one does not see the humorous side of things, one misses just a little in life.

Gen. King was introduced, and you know of him as a bright man and interesting talker; and on this occasion he lived up to his reputation. I wish that I could remember all of the stories that he told, but as his entire talk was either a story, or the introduction to another, I do not know that it is strange I remember so few. It takes a long memory for a short story anyway.

The simplest statement of facts gains a hundred percent interest if told by an interesting speaker, while the same written or told by another seems flat. I fear such will be the case now, however you are at liberty, and amply endowed with the power to supply the necessary animation. The General spoke of the pleasure he felt in being in Culpepper on this memorable occasion, etc. and was reminded that the veterans were all getting old. “My dear old mother is still living” he said, and persists in looking on me as a boy, although I fear other people have no trouble in seeing my gray hairs. A short time ago I was invited to speak at the dedication of a new church in Brooklyn, and when mother was told of the fact, she exclaimed, “Why, Horatio, why don’t they ask an old man to do it?” Touched on the flight of time he said, “Time does fly, and that reminds me of the little dark girl who was diligently engaged with a fan in trying to keep cool, and listening to the truths as told by her Sunday school teacher. “Amanda it is two thousand years since the time of Pilate.” The fan stopped and the dusky features gathered a thoughtful expression: “Two fousen yeas! for de lan’ sake now time do fly,” and the fan made up for the time lost in thought.

The Sunday school story brought to mind, one of two little boys who were each given ten pennies and told to use them, and next Sunday see if they could not bring ten more. Sure enough, on the following Sunday, Willie brought twenty nice bright coppers to show for his industry and business ability. He was of course praised and made much of, for the good use he had made of his ten pennies. The teacher then turned to Tommy and said “Well, Tommy, I trust that you have also increased the ten pennies which were given you. Tell me, how many pennies have you?” “Haint got none,” said Tommy. “You haven’t any! why, Tommy what did you do with your pennies?”

“Lost ‘em matchin pennies wid Willie.”

On touching on the depreciation of confederate money during the war, the General told that a colored man was leading a very poor specimen of a mule, and in passing a company of soldiers was made the mark for their fun.” I say nigger, “said one,” Where did you get that mule?” The black man made no reply.

“Say, Mose where are you going with that mule?” Still no reply. “I say black rascal, want to sell that mule?” The ears pricked up a little, and a faint smile brightened the dusky features, but no answer.

Now, nigger, I’ll give you three thousand dollars for that mule.” “Free fousan’ dollars! You go way boss, I dun just give a fousan to hab dat critter curried.”

We were led from story to story, and in speaking of the patriotism of the southern gentleman, Gen. King said, “I once heard a story of Col. Dudley, who lived here in Culpepper, — does any one present remember the gentleman? Well, I do not say that it is true, but this is as I was told the story. Col. Dudley had one thousand dollars which he wished to invest in a $1000. Virginia state bond. So being in New York he went to a broker and stated his business. He was given the security, and in payment tendered $1000. Now, at that time these bonds were selling at something over $900. so the broker handed back the correct change. The Colonel said, “What is this, sah?” The broker explained that the bond was worth $940. and that he had returned the change. “What, sah, “said the Colonel, a Virginia bond worth only $940. sah; keep your change, sah, and when ever you hear of Col. Dudley of Culpepper, Virginia, sah, paying less than $1000. sah, you may d—m me, sah, Good morning, sah.”

Gen. Curtis was introduced and proved to be a very interesting speaker. He contrasted with Gen. King in taking a more serous vein, and although he told several stories, they did not depend upon a joke for the point. He spoke of the pride of the southern people, and paid a high tribute to the southern women. “At the close of the war” he said, “I was stationed at Richmond, and among my other duties it was my business to give help and transportation to the soldiers returning to their homes. A short time before closing one afternoon, a young man came into the office and said, “Can you tell me sir, when I can start for my home in Alabama?” I told him communication was not open, and it would be several days before trains would be running, but that I would give him a passage to his home as soon as possible. “But, sir,” he said, I can not wait, I have no money, and the only friend I have here is too poor to help me.” I replied that I would give him rations, and he straightened up and said, “No sir, I could not do that.” I persuaded him to wait until after the office was closed, when I succeeded in making him accept help. Years after, while representing my state in Congress, a member introduced himself, who proved to be a relative of this man. He said, “Gen. Curtis, anything you want from the members of Alabama is yours, only don’t ask us to vote the Republican ticket.”

Gen. Curtis told of going to call upon a certain General during the war, and upon arriving, found the General with his staff in front of the tent inspecting some work. While talking with him a lady drove up and requested to be directed to the person in command. She said, pointing to a house not far off, “General, I live in that house, and since your troops have come, I have been cut off from my friends. I have nothing to eat or to give my three children, my servants or myself. The General said, “Madam, I can give you food upon the usual conditions.” “What are the conditions, General?” — “The oath of allegiance, Madam,” The woman”, said Gen. Curtis, “was small, but she seemed to gain in height and swell out with pride and indignation, as she answered: “No, sir, I would starve before I would accept food upon such conditions.” And she returned to her home. “Good, gracious,” exclaimed the General, “It is the sons, brothers and husbands of such women whom we are fighting to keep in the Union, she shall not starve if I can help it.” Calling the Chief of the Commissary Dept. to him, he said: “Here is fifty dollars to buy supplies for the officers mess.” Every officer contributed as he felt able; an officer was sent with a wagon and driver with a load of provisions to the lady’s home, with instructions not to say from whom they were sent. A servant answered the door, and asked the driver who sent the goods, but received no answer. The lady was called, and when she learned the situation she said, addressing herself to the officer, “Will, you tell me sir, whom I am to thank for this kindness?” “Thank the stars, Madam.” “ Yes, but on whose shoulder are the stars ?”

During the evening Mrs. Stilson sang several songs, and about ten o’clock the meeting broke up, and I for one went back to the hotel. Mr. Seeley said that he was way-laid at a church ice cream festival, and gathered around the board with ten young ladies. But then it is no trick to eat ice cream with ten young ladies — if you have the price.

I sat out on the porch with Messrs. Seeley and Newbury, and might as well have stayed there the balance of the night for all the sleep I had. I do not know what was the matter with me, but I could not go to sleep. I have heard that if one would count, when they were unable to go to sleep, that they would be dreaming before they knew it. I counted until I was in the thousands somewhere, — but than I dare say I did not count long enough. It was after three when I lost myself anyway. I had one of the three beds, and had just settled myself as another fellow came in, — he had a cot.

I went down stairs about six o’clock that morning, and in a half hour there were a number of men about. About a quarter of seven, I was standing on the verandah holding up one of the several pillars, when a man came up, ( right sleeve empty ) and asked me if I could direct him to the hotel at which Col. Brown was staying. I said that I could not, but could send him to Mr. Boyce who no doubt would be able to tell him. He said that he knew Mr. Boyce, and in fact had come a hundred miles out of his way to see Col. Brown and Mr. Boyce. He met them at Staunton twenty years before, when the 28th held a reunion with the 5th Virginia. I said, that my father, Col. Bowen, had attended that reunion. He exclaimed: “Col. Bowen! Why, I knew your father well, and your sister Emma. They were at my home, and Emma stayed and made us a visit after the rest of the party went home. I am Col. Stickley.” We shook hands, and at that moment another gentleman came up, and I was introduced to Capt. Smiley. You may imagine my feelings at this unexpected and rather romantic meeting with men whose names are familiar to me as friends of father, mother and Emma. They were both very cordial, and seemed to enjoy meeting me. Capt. Smiley spoke of father’s return to Harrisonburg twenty years before, and of the ovation he received there. He said, “I thought the people would shake your father’s hand off.”

Col. Stickley’s account of his part in the restoration of the flag to the 28th was interesting to me. He said, “I was paying attention to the lady who is now Mrs. Stickley, and as she was living in Washington, we spent some time in visiting points of interest. As we were sitting in the east room of the White House, a gentleman came up and presented Col. Brown’s card, and said that I would hear from him shortly. It seems that Col. Brown had left instructions with the man in charge of the old battle flags in Washington, to put him in touch with the first 5th Virginia man he met. I, with a friend had been looking over the records in the department to settle a dispute we had in regard to the capture of a flag. So that my name was sent to Col. Brown. This was the first attempt on the part of the north and south to hold a joint reunion and culminated in the meeting at Niagara Falls, in which the flag was returned to the 28th. You know of the identification of the flag which was done by fitting a small square, which had been cut out before the capture at Cedar Mountain.

Col. Stickley, Dr. Blackford and myself went into breakfast together. Capt. Smiley was staying at a private house as he was not able to secure accommodations at the hotel. After breakfast, Col. Stickley and I went to call on Col. Brown. The house was a red brick, two story structure, with the main entrance on a level with the street, and opening on to a broad hall. We were directed by a servant to the verandah, which ran across the front of the house on a level with the second story, and was reached by a stairway leading from the street at the extreme end of the building. We found comfortable porch chairs, and had just seated ourselves as the lady of the house came in. Gen. Curtis came in from an early morning walk, and after being introduced, started a story. Col. Brown came out in a few moments, and after meeting Col. Stickley, said to Gen. Curtis, “You finish your yarn, while I talk to my young friend Bowen.” He asked after mother and the family, and I took the opportunity of extending Effa’s* invitation to visit her when he came to St. Louis. He said that he traveled very little now, and rarely went away from New York, but appreciated her thought of him, and would certainly do so if he ever went there again.

[*NOTE: Erwin Bowen’s children were daughters Effa and Emma, and his sons were George and Harry – per Mary Z. Robinson, descendant of Capt. Bowen, Nov. 8, 2020. —B.F.]

Judge Brown, the Colonel’s son, and Dr. Adams who is attending Col. Brown, and in fact hardly leaves his side, came out and were introduced. The son of the lady at whose house Col. Brown was quartered after he was wounded at Cedar Mountain called, and they had a good chat over old times.

Col. Stickley and I had had our breakfast at seven o’ clock, but the meal was not announced until after eight at Col. Brown’s so we stayed until that time. Col. Stickley was obliged to leave for Staunton at eleven o’clock so we left.

I had made no arrangements to be taken to the battle field, and most all of the men had started by this time. Col. Brown had introduced me to Dr. Blackford before breakfast, so I was very glad to meet him as I left Col. Brown’s, and we arranged to go over to the grounds together.

I took a snap shot of Col. Stickley, and assured him that I fully intended to accept his hearty invitation to visit him at his home in Woodstock, Va. and we than said good bye.

Dr. Blackford proved to be a very pleasant man. He is a cousin of Capt. Blackford, the speaker of the day; had served as a surgeon in the Confederate army, and was at Culpepper at the time of the battle. We secured a colored man with a team, and two seated conveyance to drive us over. The distance is about eight miles. After a generous use of rope and wire, our outfit was considered strong enough, by the driver at least, to carry us to our destination. We had, however, to stop on the way several times to wire up. We had some doubt as to the ability of the team to take us there, even if the harness could be persuaded to hold together, but we drove the distance in just an hour. We had some fun with the colored man on the way. Dr. Blackford said, “See here, boy, I don’t believe that team will ever take us over.” The “boy” grinned, and replied “Doan you fret, boss, if any body git dar dis nigger gwine be dar, too.” “Yes,” I said, “but what is the use of being there after everybody else has gone?” “Go way, boss, we’s gwine be dar shure.” A team started just ahead of us, and our man had been waiting for another “Dollar” to fill the one vacant seat, so we said, “Now, Captain, if we had gone on that wagon, we would have been there now.” “When dat wagon git dar boss, you just look ‘roun, and you see dis nigger right behind.” Nobody aint gwine to lose dis child.”

The road took us through the main street of the town, and turning to the left, passed the old “Culpepper Court-House,” which is now a private dwelling. A mile out of the town we had a splendid view of the surrounding country with Blue Ridge Mountains to the west. Along this road, forty years before the boys of the 28th were marching; some to Libby and Belle Isle, and others to the great unknown. I could see the brave 28th, as they trudged along, hardened veterans now. Each one intent on the stones which lay in his way, or shifting the load he was compelled to carry. There was no worry lost they were out of step; no thought as to the appearance they made, for this was war, and they had learned the difference between a dress parade and a march. And there is the flag hanging limply from the staff as though it knew that this was the last march it would take with the boys who had defended it so bravely. ‘tention Company! Shoulder arms! For’ard ‘arch! and I see the company swing past.

The Regiment started from Culpepper, a distance of about eight miles on the road to Orange Court House, and camped the night of August 8th near Cedar Run, which at this point at least is a mere brook, and is about a mile from the battle field. On the morning of the 9th, they were moved about a mile further up the road, and lay in a piece woods, nearest the position from which they charged in the latter part of the afternoon.

Forty years of course must make many changes, and yet in this country district, at exactly the same time of the year, I could certainly imagine myself seeing the country as father saw it. All this day I lived father’s life of forty years back. My imagination pictured him, as he looked and acted, and you who are sentimentally inclined will probably understand, and would have had as much trouble in keeping the tears back, and succeeded no better than I.

Well, to come down to the present again, I am sure that you would have enjoyed seeing the assortment of wagons, carriages and what-nots, which are pressed into service, and lined the road from Culpepper to the battlefield.

There were lumber wagons, with the family sitting on the straw covered bottom; others had the dining room chairs arranged like an eight seated wagon, while others were satisfied with boards laid across the top of the box. As I expressed in my letter, there was everything from a stone boat to a coach and four, the two extremes excepted. People came from miles around, and when I arrived at about half past nine, the fence was lined with teams, and the woods were literally full of them.

The exercises were to be held on the spot where the Regiment camped the night before the battle. Not from that fact, but as there was a small church there, it was the best place for the speaking. I was afraid that I would be too late to find any of the men, as they had all left for the battlefield when I arrived at the church. I lost no time in getting up there, however, and after a time found Messrs. Seeley White and Baker, and was shown the different points of interest. At the entrance of the woods where the Regiment is supposed to have charged across the wheatfield, a marker has been placed. All were sure, however, that the exact spot was several hundred feet north.

[Note, I believe the house in the right, background may be the Throckmorton home. The family, related to the Crittendens, would entertain the veteran soldiers who returned after the war to tour the battlefield. The house was torn down in 2012. -B.F.]

Mr. Seeley pointed out the line of the charge: the location of the fence, road, woods and battery at the time of the battle. Mr. Baker told me of father’s capture. He said, “I was captured right about here. I came back out of the woods and found our boys being taken prisoner, and decided that there was no chance, so I pitched my gun over into some water which, I suppose, must have been in this little ditch, and dropped down to await developments. No one seemed to pay any attention to me, so after a time I got up, and just then your father came out of the woods, and he was waiving his sword, and did not seem to intend surrendering, and I was afraid that he would be killed. I said, “Captain, its no use,” and he replied, “Presently sergeant, presently, and then surrendered. I took sergeant Baker’s picture on the spot, but am sorry to say it was a failure. Mr. Seeley’s picture was taken in the same place, so that it not only gives a good view of the wheat field, but also locates about where father was captured.

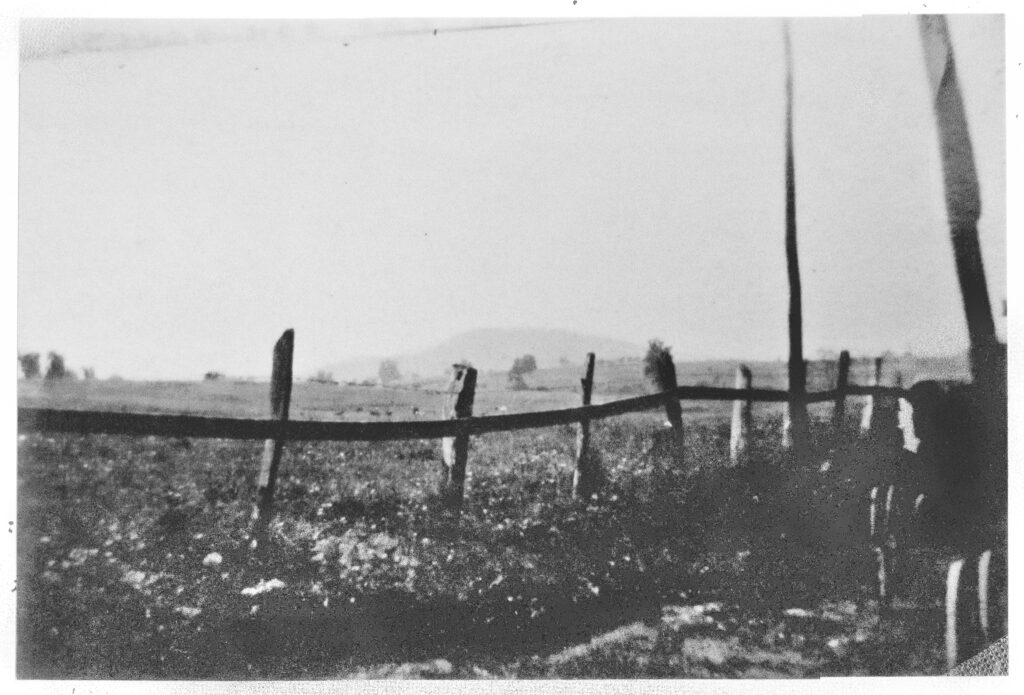

The picture was taken by the road looking back over the line of the charge towards the woods from which the regiment started. This field was bounded on three sides by woods: the left side was open ground or possibly wheat, and across which the 5th Va. charged in turning the 28th’s flank. Another picture shows the woods to the right, while another is looking from the starting point towards the mountain. This part has been changed as there is a house there now which was not there then. At the left of the house is the point at which the confederate battery was located.

Mr. Brace of Shelby, a brother of a 28th man, had found a mini ball while looking over the battlefield. I had picked up several small stones intending to keep them as a souvenir of the trip, and thinking the children might care for one. But when I saw a mini ball, I decided that one would be a very much better keep sake. I did not seem to have any luck, however, and when Mr. Brace found another, I exclaimed, “Well I wish I had your luck” . He replied, “I am afraid you look too hard, but the next one I see I will point out to you, and you may pick it off of the battlefield.” He soon found another, and I picked it up. It was very kind of him and I of course told him so. Up to this time Mr. White had tried very hard but had not been able to find one, so I told him that Mr. Brace had been kind enough to let me pick one from the battlefield, and that if I were able to find one I would return the compliment to him. I was able do do so, and he was very much pleased. He said that he wanted to take it home to his boys. His brother was killed at Cedar Mountain and is buried among the unknown dead at Culpeper. I later found another bullet, so that I was able to pick one up without any help. Mr. White and I were the last to leave the field as we thought we could hear a speech, or have a dinner any day, but could not visit the battlefield as well. About one o’clock we started back to the church. The ladies of Culpeper had prepared a dinner or standing lunch, which was served between two long tables built for the occasion. There were a number of men drawn up in line, and among the number I saw Capt. Smiley and Col. Williams of the 5th Va. I went up, and was drawn in between them, and commanded by Gen. Curtis I was marched off with the enemy to dinner. We were lined up in front of the pine board tables, behind which stood the feminine beauty and youth of Culpeper. Each person was handed a wooden plate filled with fried chicken and other things. Capt. Smiley and myself went in search of a drink of water, after which we wandered about the grounds. I took the opportunity of taking a picture of Capt. Smiley and his son, and probably very near the place where the 28th camped, the night before the battle. Earlier in the day I took a picture of Cedar Run showing a team crossing. The camp was to the right of this stream.

Capt. Smiley was most cordial in his invitation to visit him, as was also Col. Stickley, and I was very sincere when I told them that I should look forward with a great deal of pleasure in doing so. Capt. Smiley was quiet and dignified, and made me think of father. Later I met Mrs. J. M. Beard who was Miss Mary Smiley, and Mrs. Clemmer. Mrs. Beard talked of Emma and spoke of the pleasure they had in her visit. She recalled a visit they had from a young man whose pockets they filled with small pumpkins. Mrs. Clemmers told me of the handsome young ladies she would introduce me to when I came down to Virginia, and when I regretted the fact that I was a married man, she said she did not believe it because I had too much hair on my head. I told Mr. Clemmer that I could now account for his bald spot.

Capt. Smiley had to leave in the early part of the afternoon and I left him with the assurance that I should look forward to my trip down the Shenandoah Valley, and a visit to his home. The captain and family wished to be remembered to our family, and spoke several times of their pleasure in Emma’s visit.

During the remainder of the afternoon I wandered about the grounds. I heard very little of the speaking because it was impossible to get a seat, and it was very tiresome standing. I took several pictures of the grounds, as well as one of Mr. Roberts. The later I am sorry to say was a failure, as were also those of Messrs. Baker and White. I am especially sorry that these pictures did not turn out well, as I wanted to have pictures of company D men which were taken, at the reunion. The man who captured the flag was present, and I thought that it would be interesting to have his picture. He did not have a very rough time taking the flag as they were simply handed to him by the color bearer as he surrendered. I was tired enough to be willing to go back to Culpeper before the exercises were over, and spent an hour in looking for Dr. Blackford and the driver. I at last decided that they had left, and secured a seat in another wagon. The driver was a native of Culpeper and had served in A.P. Hill’s division. He pointed out interesting land marks on the return trip, such as the two hills from which Grant and Lee kept watch of each other.

I found Dr. Blackford on my arrival at the hotel, and learned that he had decided that I must have come back, as he was not able to find me. I told him that I had asked Capt. Blackford if he could tell me where he (the doctor) was, and he said that if there was any eating or drinking around I would find him there.

The train for Washington was due at 7.15 P.M., so that we had plenty of time to remove the generous supply of Cedar Mountain soil which had collected on us, and also to enjoy another, and last Virginia supper. Arrangements were made to have the through train stop for us, and I would have been able to connect at Washington with the ten o’clock train for Baltimore. The train was very late however, and I barely had time to change to a train which arrived at union station ten minutes of twelve. The last car for Cantonville passes the city hall at just midnight, and I was very much afraid that I would miss it. As it was I had just one minute to spare, and that was because the car was not on time. The city hall bell struck twelve as I reached the corner.

I came home with a greater desire than ever to visit the Shenandoah Valley, and with a firm intention of doing so in the not too distant future.

In closing this little account of my trip, I regret that I have been unable to express fully my impressions, but I will take this opportunity of inviting the family to make the trip with me, when I will supply the necessary information, and you can do the rest. But the opportunity of meeting with, and enjoying the enthusiasm of the survivors of company D on the field which has had such a romantic place in our thoughts: the privilege of having our earlier dreams brought to a realization by the men who formed a part of them: this chance has passed, and as I think of the great pleasure I had, I am thankful that I was given, and took advantage of the opportunity to be present.

EPILOGUE

A member of the Bowen family has visited CM every generation since since the battle.

NOTES:

- A Brief History of the Twenty-eighth New York State Volunteers; by C.W. Boyce, p. 89-91. [Accessed on-line at internet archive.]